Dancers' Stone – my new special spot in Norway.

I stumbled upon this noteworthy rock while driving through Telemark’s countryside. I was on my way to Rauland Academy, a traditional crafts school, and decided I needed to take a break in the woods. I had been traveling for three weeks straight, and was almost never alone during that time. Many people generously hosted me at their homes and I was on public transit quite a bit. So on my trip to Telemark, I rented a car so I could have some independence and solo time.

View from the drive through Telemark.

On the windy road that passed mountains and rivers, I noticed a sign that had the icon of a hiker. I passed it and then realized that that hiker needed to be me. I did a u-turn and followed the sign onto a dirt road, past wetlands, farm houses, and up and up and up. The road was called “Fjellvei” or mountain road, so I suspected it would at least lead to a view of sorts.

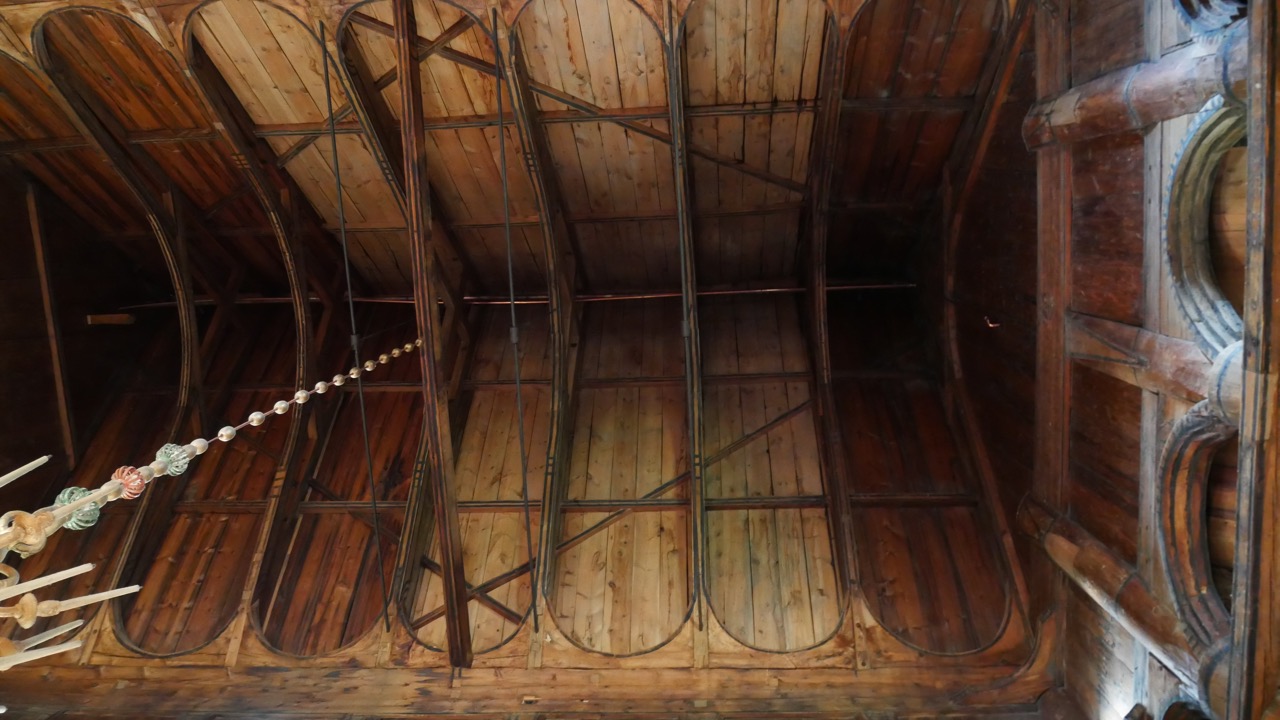

I had to drive a ways up this road past cabins and homes, but finally the scenery changed. The landscape was filled with glowing green lichen, moss and my new favorite tree, fjellbjörk, or mountain birch. I found the launch point of the hike, and made my way up the trail. Expressive fjellbjörk lined the path.

Curvy fjellbjörk.

One looked like it was welcoming me amidst a dance twist. I remember thinking to myself, “am I about to meet my spiritual guide or something on this hike? What is this place!?”

Dancing fjellbjörk

Have no fear, travel magic is here. I kept climbing up the mountain, not another (human) soul in sight, and suddenly got to what I’ll call an alpine meadow. There was an opening of the trees and only grasses blowing in the wind. Très belle! Or should I say, Tre belle! ("Tre" means "tree" in Norwegian.) Hee hee - gotta love multilingual puns that have a highly limited audience!

Alpine meadow on the hike.

It was 6 at night, but the sun was filling the scenery with a kind of white brilliant light I’ve only seen in the Scandinavian summer.

After climbing past the meadow, I came upon a wooden sign wedged between two fjellbjörk branches.

Sign at Dancers' Stone.

It read:

THE DANCERS' STONE

IN FORMER DAYS OLD AND YOUNG PEOPLE GATHERED HERE TO DANCE AND AMUSE THEMSELVES. A LOT OF FAMOUS RIDDLERS HAVE PLYED HERE.

DANSARSTEINEN

GAMLE DAGAR SAMLAST UNGE OG GAMLE PÅ DENNE STEINEN TIL DANS LEIK OG MORO. ...YLLARGUTEN-JON KJOS OG ANDRE KJENDE...PELEMENN HAR SPELA HER.

That dancing fjellbjörk I saw earlier on the trail must have been a part of this tradition as well. I spoke with folks later on in my trip who knew people who played filddle on this rock and danced as a celebration of midsommar, or summer solstice.

Being the only person on the mountain, I blasted Kiesza’s “Hideaway” and put my own twist on this timeless tradition.

Dancer on Dancers' Stone.

Dancers' Stone in the distance.